Justin Strauss

"Every club was packed every night of the week - Limelight, Tunnel, Palladium, Area. I don't know where all these people came from."

A quick note for those of you in NYC: I’ve collaborated with MOMENTNYC on an event at Rubulad in Bushwick this Sunday (Feb 2), celebrating NYC’s rich history of residential DIY venues. I’ll be introducing a screening of Alan Lomax’s short film Ballads, Bluegrass, and Blues, which documents folk and blues musicians performing in Lomax’s Greenwich Village apartment in 1961. Following that, the Underground Producers Alliance will present previously unreleased footage and recordings from Studio We, the influential mid-’70s L.E.S. jazz loft venue , and Joe Ahearn will talk about his life at the Silent Barn, a seminal ‘00s/’10s Ridgewood DIY space where buzzy indie bands performed in front of the kitchen sink. This is not to be missed! Grab advance tickets here.

When I first discovered Justin Strauss, I assumed there were two of him. There was the lead singer in Milk ‘n’ Cookies, a short-lived but phenomenal power pop band from the early years of CBGB. And then there was the celebrated deejay and remixer who’d been spinning cutting edge dance records ever since the Mudd Club’s late ‘70s heyday; who’d gone on to play at the Ritz, Area, Limelight, and Tunnel, among other fabled venues; and who remains a fixture behind the booth at every NYC club worth its salt. These Justin Strausses seemed so musically disparate that it took me an embarrassingly long time to put two and two together.

That kind of fluidity between musical eras and genres in NYC is a central component of my work, so once I began work on my book, there was no question that I needed to interview Justin. But despite the fact that he has almost literally seen it all, I was most impressed by his enthusiasm for the present. When we spoke in October 2021, he was unreservedly stoked about the city’s contemporary dance scene, and also mentioned having been recently impressed by the Williamsburg indie folk venue Pete’s Candy Store and the post-punk band Parquet Courts.

That open-mindedness has kept him at the heart of NYC’s nightlife and youth culture in a way that few (if any) of his peers can match. In the last four months alone, he’s spun alongside “indie sleaze” king the Dare at one of the latter’s notorious Freakquencies parties, and reunited Milk ‘n’ Cookies to open for their Gen Z spiritual heirs the Lemon Twigs. In keeping with that spirit, I should note that Justin recently updated his answer to my final question so as to address NYC’s contemporary nightlife landscape.

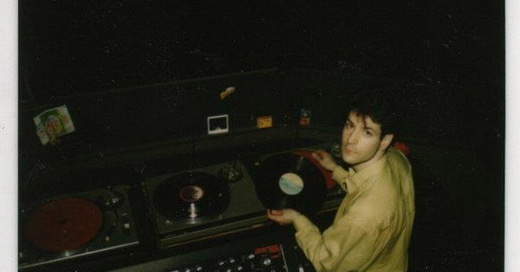

Photo courtesy of Justin Strauss

What was your initial introduction to nightlife or underground culture in the city?

I started very young, because the first time I stepped into a club, I was about nine years old. I had very cool parents, and my dad was into music. He was a painting contractor, and he got the contract for this club that was going to be opening called the Electric Circus. He would take me to work with him during the day, and then he would take me at night when the club opened. So I was 9 or 10 years old, and I saw Sly and the Family Stone. I would beg him to take me, because it blew my mind. They had overhead projectors with gel lights and it was quite an immersive experience, so I set up a little club in my basement in Long Island modeled after it. I put up aluminum foil on the walls and had movie projectors going.

I started going out on my own when I was young, like 15 or 16. Me and my girlfriend would sneak into Max's Kansas City, Studio 54, and Club 82 - as many places as we could get into. I was enamored by the whole Warhol scene; I would sit at home and devour Interview. To actually be in the same room with these people was amazing.

Where on Long Island were you?

Woodmere, on the south shore. I hated it. But I was always [going] to the city. My dad would take me and we’d go record shopping, stuff like that. Before I started driving, I’d take the train into the city on my own. It was so vibrant and exciting to me. When I met the guys in Milk ‘n’ Cookies, we connected over our love of the same kind of music. So I found my little group, and I had my girlfriend, and we just kind of made our own world there.

Do you remember the first Milk ‘n’ Cookies show in the city?

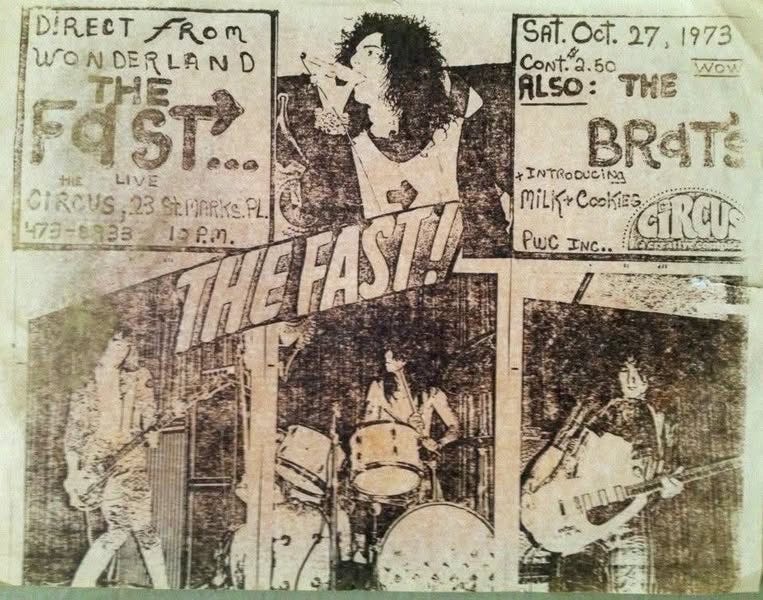

Crazy enough, it was at the Electric Circus! It was past its prime, and it wasn't the original people involved. It was just called “the Circus.” We had become friends with a group called the Fast, and they invited us to play our first gig in the city, which I think was around in October 1973. They were a really important band, one of the first bands that was doing stuff like that, and they helped other bands. We owe a big debt to the Fast.

There wasn't CBGBs [yet], there weren't a lot of places to play. There was Max's, but Max's was booking more established acts at that time. I saw Iggy and the Stooges there, Sparks, Cheap Trick playing for like 10 people. There was a club in Queens called the Coventry, where Kiss started out, and [New York] Dolls played there, so we played there as well. But that wasn't quite “New York City,” that was Queens.

Flyer courtesy of Justin Strauss

Did you move to the city once the band started taking off?

I couldn't! I didn't have a job. I was 17, 18 years old. I was supposed to be going to school. When we got signed to Island Records, it was my last year of high school. And then we went to England.

Once you started playing shows regularly in the city, was there a club that felt like a home base to you?

We went to England to record our album, and by the time we got back, the CBGB’s thing was starting, and Max’s had [started hosting] unsigned bands. So between Max's and CBGB’s, we’d play back and forth, like pretty much every band was doing back then. We started playing with Ramones, Talking Heads, Television, and Blondie at both of those places. We were very tight with the Ramones, so we played a lot of shows with them.

It was a really small scene. People don't realize that it was basically just the bands. The audience had started to come, but [the audience was mostly] just the bands. If they were charging, it was two bucks or something, but I don't remember paying. Since you’d played there, everyone knew you. Everyone would go see everyone else's shows. I don't know how anyone made any money. Money wasn't something anyone was thinking about, that was very back burner. We were just happy to be doing it.

How did you view the difference between the first era of Max’s under Mickey Ruskin’s ownership [1965-1974] and the second under Tommy Dean [1975-1981]?

When I started going to Max's, it was the Warhol scene. Getting into the back room was the biggest thing in the world. Everyone that I was reading about or listening to was there: Iggy, Bowie, Todd Rundgren, all these incredibly interesting Warhol people. Upstairs, there were newer major label artists who were playing this small place, like Bruce Springsteen. When Tommy Dean took it over from Mickey Ruskin, they were basically doing the CBGB’s vibe with unsigned bands. It was a much younger crowd - kids, punks, all that stuff.

When did you actually end up moving to the city?

The band moved out to LA at some point in 1977. We thought that would be fun and/or a good idea. We had come back from England with our album, there were all kinds of delays, and we were getting very frustrated. Our first single had come out, and Island Records wasn't quite sure what to do with us now. Our bass player, Sal [Maida], got an offer to go play with Sparks around 1976, and he moved to LA. He called me one day and said, “You’ve got to come out here. Everyone loves Milk ‘n’ Cookies. You guys could do really well.” So we flew out there, and I moved to the Tropicana Motel.

All these things were gonna happen, but two years had gone by and nothing happened at the end of the day. I was really missing New York and wanted to come home. I was talking to my ex-girlfriend, and she was like, “There's this club that just opened called the Mudd Club, and it's so cool. You should deejay there.” And I was like, “I don't deejay.” I had a ton of records, but I’d never thought about being a deejay. She said, “Just come. I'll introduce you to David [Azarch], he's the deejay there, and see what happens.”

So I came back to New York and went to the Mudd Club. I met David, and he asked me if I would like to try it one night. I was nervous as hell. I remember my hands were shaking when I was putting the records on. I'd never done this before in my life, but somehow, I guess I did okay. Steve Mass, who owned the club, asked me if I wanted a night there. And at that point, I decided it was time to move to the city, and it was around at that time, either late ‘79 or ‘80, that I got an apartment.

Do you remember the first record you put on that night?

Oh god, I wish I could. I packed a lot of soul, a lot of funk, some glam…there was a ton of new music coming out time. You had punk rock, new wave, hip hop, all these new forms of music being born. And even though the Mudd Club was supposed to be anti-disco, I would sneak in some of that too when I felt more comfortable.

There was a lot happening then, a lot of creativity. You had the art and the music world really close together, which is something that doesn't seem to happen much anymore. You had artists doing music, like Jean-Michel [Basquiat] with his band Gray. You had Keith Haring hanging out every night, and Andy was everywhere.

You mentioned having gone to Studio 54 earlier. Did you have much of a sense of what was going on in the dance music world at that point?

Studio 54 [would play] the popular disco records of the time: “Ring My Bell,” “In The Bush,” France Joli, lots of Diana Ross. We also went to Infinity and 12 West a few times. But all of this was before I even thought about deejaying. Once I did start at the Mudd Club, I got turned on to some really cool left-field disco records, so I played some of those. I loved the records Arthur Russell was involved with. I had bought some early disco 12” records and was fascinated with the concept of “the remix,” and you started to hear that influence crossing over to new wave records as well.

But it wasn't until I went to the Paradise Garage, not long after I started at the Mudd Club… That was a revelation for me, with all this music that I did not know and totally fell in love with. Going to that club for the first time changed everything I thought about deejaying and dance music.

The very first time I went, my friend [and fellow Mudd Club deejay] Ivan Ivan got us on the list somehow. The second time, François [Kevorkian] took me. He took me up to the booth, and that was when I met Larry [Levan] and we became friends. I would go there every Saturday night after my gig. When I was working at Area, it was close by. Area would close at 4:00 or 5:00 in the morning, and then we'd go to the Garage until noon or whatever.

Justin in the booth at the Ritz. Photo courtesy of Justin Strauss.

François was a big inspiration too. He was the first deejay that I saw doing all these crazy beat matching things and overlaying records. Watching him, I picked up a few things, and I started incorporating that kind of thing into my sets. That was later on, when I got to the Ritz, because they had actually had three turntables. The setup at the Mudd Club was really janky, it wasn't a very professional setup to say the least. It was two home turntables and some really primitive mixer. It wasn't about mixing records there, it was about just connecting the dots for me with all this music that I loved, and making it sort of work. Anita Sarko was incredibly innovative, and Johnny Dynell was fantastic - both of them were deejays at Mudd Club as well.

But that was the turning point for me: the Garage, François, understanding the concept of what a deejay really can do, and how, how it can take you on this…I hate to say “journey,” which sounds corny, but you build the night up and go somewhere and have different experiences through the night.

Were there other people you knew who were coming from a similar punk background who were also going to these places? Or were you alone in that regard?

I wasn't alone. Mark Kamins, I don't know that he quite came from a punk rock background, but he came from a more alternative background, and he was playing at Danceteria while I was playing at the Mudd Club. He was totally innovative, layering Arabic records and world music, all kinds of things over other things. He would go to the Garage too. I would say it was a pretty small group. It really spoke to me in a powerful way, and I know it did to Mark too.

I think we were probably the two [from that background] that were really turned on by Larry and that whole thing. Neither one of us copied what he was doing, but we brought some of that feeling and creativity we experienced there to what we were doing. Larry would also come to hear what we were doing at those clubs and started playing Liquid Liquid, ESG, Talking Heads and those types of records at the Garage, which was fantastic.

Did you go to the closing weekend at the Garage?

Oh yeah. A lot had happened since [I’d first started going there]. AIDS obviously impacted everything in club life, because so many important people got sick. I remember working at Area when we first started hearing about this thing, and no one knew what it was or how people got it. Did you get it from drinking a glass at a club? We didn't know. There was no information.

All of a sudden, people stopped coming. Klaus Nomi was the first person I knew who all of a sudden just died under these mysterious circumstances. When I think about how many people I knew that passed away from AIDS…it was shocking. It wiped out a lot of people. I think that had a lot to do with the way things started changing. So many creative people who made this scene vibrant weren't around. On top of that, gentrification was bringing in less interesting people with more money.

Can you pinpoint the moment you started to notice gentrification?

The most obvious change to me was in Alphabet City. Avenue A is like Park Avenue now, but back then you could get killed. B and C, you just wouldn't go there. There were shootings and muggings and all kinds of crazy shit. When I go there now and see gazillion dollar apartments and people wanting to live there, it’s still a mind-blower to me.

It wasn't like it was gradual, it happened kind of quickly. Giuliani was cracking down on nightclubs and making it really impossible for a lot of places to operate. All of a sudden, people with money were moving into nice buildings that were next to clubs that had been there for years. They would complain about the noise and the crowds, and even though [the clubs] were there first, they had people's ears in the right places and were forced to close. Club were being priced out as well.

Another club, where Downtown and Uptown met in a weird way, was the Palladium, which was a huge club. They were involved with the artists - Keith Haring painted the backdrop, Kenny Scharf did a whole room, Jean-Michel had stuff all over the place. It was a really great club for a while. Larry played there for a time, Junior [Vasquez], I played there a bit. Every club was packed every night of the week - Limelight, Tunnel, Palladium, Area. I don't know where all these people came from.

The door person was so crucial, letting in the right mix of people. People like Haoui Montaug, Richard Boch, Gilbert Stafford, and Sally Randall were vital to the scene.

My two favorite clubs ever were Area and the Paradise Garage. I spun at Area, I obviously didn’t spin at the Garage. But for me, those were two very special places. What Area did at that time, changing the themes and totally transforming the club every six weeks…I don't even know how that happened. You wouldn’t even know you were in the same place! I couldn't imagine something like that happening today.

When places like the Garage and Area started closing, did any clubs open that felt like a continuation of that lineage?

The guys from Area, the next thing they did was MK, which was a club in a townhouse across from Madison Square Park. That brought some of the aesthetics and weirdness of Area, but they also had a restaurant. The World was a really great club; Larry played there, and Frankie Knuckles as well.

But you saw things changing. What was next was [mostly] huge clubs like Sound Factory and Twilo, and then after that bottle service places. People were moving out of the city or dying, so we were losing a certain element of what had made these places so special. It was a combination of the club, the people who went there, and the music. When one of those things goes away, the balance is off and it starts to go in another direction. It became less interesting.

What about those smaller post-Garage parties that were going on in the ‘90s, like the Choice or Wild Pitch?

Yes, those were great parties and had their own unique vibe for sure. Maybe I was spoiled by being able to go to the Paradise Garage every weekend. There are people who were turned on to this whole club scene [by going to] the Choice or the World, so I'm not dismissing those at all, because I know they were really important. At that point, I had been doing a lot of studio stuff - remixes, productions - and I was focusing most of my energies in that direction. I loved Wednesday nights at Sound Factory Bar where Louie Vega had a residency during that brilliant Masters At Work era.

We didn't even mention the Loft, although I was much more of a Garage head than I was going to the Loft. I loved the way Larry mixed records, rather just playing one record after the other. But I would go to the Loft every now and then. And it still goes on, there are these younger kids that I know that are obsessed with the Loft now. It's their connection to whatever that was back then.

I don't mean this as a diss or anything, but the Loft without David Mancuso or the Garage without Larry Levan doesn't make sense to me personally. That's why I went to those clubs. Just being in the club was such an important part of it, the way Larry controlled the whole atmosphere, the lights, the temperature, everything was to his taste. But I think it's great that younger people who weren't around can get a taste of what that was like and be inspired by it. For me, Danny Krivit’s 718 Sessions is the best example of that now.

But recently, there's been a revitalization of clubs in Brooklyn. There is a very healthy club scene in New York now. Bossa Nova Civic Club really started a great scene in Bushwick years ago. Good Room is incredible, I love playing there. Elsewhere, Jupiter Disco, Nightmoves, Gabriela - the list is endless. And they're all packed! So there is that kind of thing happening again where people are going out a lot.

There was also a spot in the city which was super cool that I thought was going to be the saving grace of Manhattan, which was Santos Party House. When I first went, I was like, Oh my God, New York City is back! But it just didn’t last. Kids who lived in Brooklyn, they didn't want to come to the city. It's really hard to do a party in the city that's cool, because they have no reason [to come] - everything they need is in Brooklyn. They have Bossa Nova, they have Paragon, they have Mood Ring. If they want something over the top, they have Avant Gardener.

Every party I play at is in Brooklyn, with some rare exceptions. Le Bain has been booking amazing deejays since day one, and now more recently there is Outer Heaven and Jean’s where I play regularly. The people from Baby All Right just took over the space that was the Pyramid Club [and turned it into Nightclub 101]. So there is some hope. To have no nightclubs in Manhattan that are worth going to, in my opinion, seems insane.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity, brevity, and context.

---------------

Follow Justin on Instagram and Soundcloud

Listen to his amazing final set at Area, recorded on 3/15/87

Order a signed copy of my book This Must Be the Place here

Book a walking tour here

And of course, if you haven’t already…