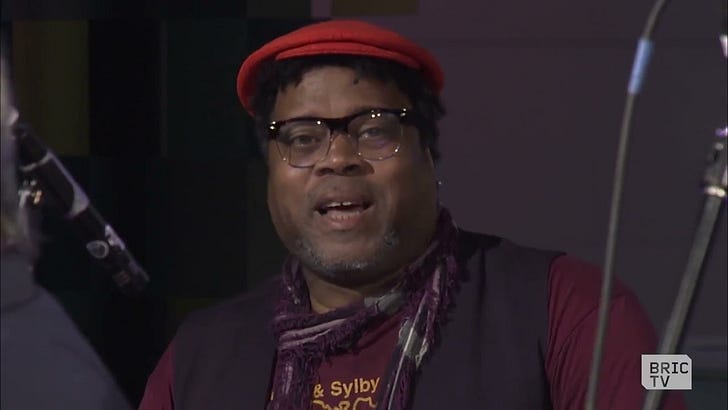

Greg Tate, 10/14/57-12/7/21

"People try to act like the music stopped at a certain point, because it stopped for the young white rebels at a time. But that’s when BRC and hip-hop were just getting started!"

One of the first interviews I posted on here was a shortened version of my June 2021 conversation with Greg Tate, the masterful writer and musician who tragically passed away six months later. To honor what would have been his 67th birthday yesterday, and in celebration of his monumental legacy, I’m now sharing the full transcript of our conversation.

I was scared shitless about interviewing Greg Tate. How could I, a music-writing newbie, ask the greatest music writer in the world to let me interview him for my book? It felt like asking Paul McCartney to watch me strum a G chord and give me notes.

And honestly, calling him “the greatest music writer in the world” hardly covers it, although his work for the Village Voice and his essay collections Flyboy in the Buttermilk and Flyboy 2 are essential reading for anyone interested in music and culture. But Tate was also an accomplished guitarist and the driving force behind two fantastic bands, Women in Love and Burnt Sugar Arkestra. He co-founded the Black Rock Coalition, which continues to advocate for Black musicians in rock ‘n’ roll. He was a poet, an educator, an activist, and seemingly a million other things besides. The word “genius” tends to get thrown around willy nilly, but Greg Tate was an actual, honest-to-god genius.

When we spoke over Zoom in June 2021, I was immediately struck by Tate’s generosity, approachability, and warmth. What was supposed to an hour-long interview stretched to nearly twice that, and I left in awe.

Greg Tate unexpectedly passed away on December 7, 2021, six months after our interview. I won’t be so presumptuous as to try to eulogize someone I only spent two hours talking to, so I’ll just say that I’m grateful to have had a chance to learn from him over those two hours. The world is immeasurably worse without him.

With all the different genres you were writing about in the ‘80s — punk, jazz, hip-hop, and so on — did you find that those communities were overlapping or interacting much, or were they pretty discrete?

The thing was, you had subcultures on top of subcultures. Everything was happening between 23rd Street and Canal Street, so everybody saw everybody. You had situations like Peppermint Lounge and Danceteria where they were booking [both] bands and deejays for [the same] night. Danceteria had three floors; you probably had three bands playing on each floor and deejays mixing music up. So it was pretty normal if people were into a lot of different things, so long as it was Downtown and cool and you could dress like you wanted to and bug out.

Did you feel any sense of distance from it, not living Downtown? [Tate lived in the same rent-controlled apartment in Harlem from 1984 until his passing]

No, because my first job was in Tribeca — the gallery I came up to work for, JAM [Just Above Midtown] Gallery, founded by Linda Goode Bryant. And because I was already writing for the Voice, I was more in the Village than I was Uptown. That went on for probably a good fifteen years or so, because if you were checking out the music scenes that I was checking out, that wasn’t happening in Harlem yet. It took a long time — really not until the 2000s — that you got people who were programming the same kind of music Uptown [as] Downtown.

How did you first meet Konda Mason and Vernon Reid? [Tate’s Black Rock Coalition co-founders]

Vernon I met around ‘80 in D.C. at the 9:30 Club; he was playing with Defunkt. Konda I think I met first because she was she was managing an all-woman rock band – Isis, I think that was the name of the band - and she got in touch with me because she wanted to put them on my radar. And another founder, the music producer Craig Street, he worked at the [JAM] gallery where we held our first meetings.

Was JAM still on [178-180] Franklin Street at the time?

No, they had just moved to [503] Broadway between Broome and Spring. It was just getting off the ground when the Republican blowback against avant-garde art got all the funds snatched off. My man Andres Serrano did a piece called “Piss Christ” that set off the Reaganites, and that was kind of the end of funding for free-thinking, radical, queer, Downtown visual art.

Once whatever funding you got from the state went away, it was like, you’re on your own, figure it out. Linda decided she wanted to get out of the art world altogether anyway, so it wasn’t a tough choice to let it go. But we launched the BRC out of that space, did our first public events out of there, and really built up a membership. I would say that JAM and CBGB’s were fundamentally crucial to the early days of the Black Rock Coalition.

Was the BRC’s formation spurred by any specific experiences around Downtown venues?

Well, all those all those bands that were around in the early 80s — Kid Creole and the Coconuts, James White and the Blacks, Defunkt, Basquiat’s band Grey — all these bands were playing in the same Downtown circuit. This is still that post-punk, new wave, two-tone era, so it wasn't unusual for folks of color to be in these bands. It was pretty normal, actually.

But we were responding to what was happening outside of [the Downtown scene]. Black bands doing rock were not being signed by major labels, who were just totally flummoxed and bewildered by the whole prospect. They would frequently tell Black bands doing rock, “We wouldn't know how to market you.” Then Living Colour blew up — like, these are the people you can’t figure out how to market?! The guys who were signing bands to labels just refused to believe that you can have a rock band with anybody but a skinny white guy in front of it and suburban America could relate. We're so far past that curve now, but at the time, that was the gatekeeping.

Vernon [Reid] had already established a relationship with Hilly Kristal at CBGB’s. Hilly really, really liked Vernon. So when we came to him and said we wanted to do a two-night music festival, they were completely open.

The remarkable thing about those shows was that that was probably that was the first time that many Black people that ever been in CBGB, because we pretty much packed it. That was also kind of the first meeting of the Black community with CBGB’s, and with the hygienics of [CBGB's], you know? [laughs] But folks really came out and supported us.

Where did that “Stalking Heads” name [for that festival] come from?

Naming the festival “Stalking Heads,” there was kind of a reverse colonialism thing going on. It was a nice little pun that said a lot. But also “heads,” like folks — the cognoscenti, you know?

And that happened right around the same time that David Fricke at Rolling Stone got interested in covering the BRC. He gave us these lavish six-page spreads with color photos, and wrote about each of the bands and the personalities, so we were off to a great start. And then after that, our bands were regularly playing at CBGB’s, and some other clubs around town like Tramps and the Knitting Factory.

And this is also around the same time that the jazz loft era [which Tate had covered for the Village Voice – ed.] concludes, because all those places start to close or get kind of pushed out.

Pretty much. I would say by the time we were starting up, a lot of places folded, but the Knitting Factory really picked up the slack. The booking of seven or eight places that had been going strong from ’75 to ’82 just became concentrated at the Knitting Factory. They became a mainstay.

Do you think the shift from these residential venues to more commercial entities like the Knitting Factory impacted the music that was being made at all?

No, no, because Knitting Factory got into it to support that same music. I mean, Michael Dorf and all those guys, they saw a void and really filled it.

Did your experience of these spaces change when you made that move on to the stage, from the audience or critic perspective?

Oh yeah, man! Anybody who's been doing criticism, you're pretty much operating at a Lord and Master level. [laughs] As soon as you move into performing, you get humbled real quick. To actually be up there in front of people and be responsible for holding it together – and at that first gig, we definitely didn't hold it together. My friend Michael Gonzales told me, “Me and my friends came just to see you fall on your ass,” and we didn't disappoint!

You said before that the stuff you were interested in only started getting booked up in Harlem around the early ‘00s, something like that?

There was a space up on the campus of the City College, it’s now called Harlem Stage. They started programming Black avant-garde theater, music and dance around ‘93. They asked me if I would be interested in doing a collaboration with my friend, Butch Morris. We produced a play of mine up there that Butch did music for in ‘93. That was kind of the beginning of the “Downtown goes Uptown” kind of move, because they were booking a lot of folks in the dance community and the music community who were known for being part of Downtown.

That's also kind of around the same time that all these venues Downtown start disappearing.

Exactly, exactly.

How does a place like Tonic fit into that landscape?

Well, Tonic picked up the slack from the Knitting Factory. John Zorn realized, once the Knitting Factory was opening their West Coast space, they were kinda losing interest in New York. And Tonic was around just as Burnt Sugar were getting started.

They were doing interesting deejay nights too, because Tonic realized that there was a younger audience that would come out for experimental music, especially if it was connected to drum and bass, hip-hop, trip-hop, and the whole illbient thing that was happening [with] DJ Spooky, and then Howard [Goldkrand] and Beth [Coleman] who did those festivals in the tunnels that are in the Brooklyn Bridge, up until 9/11. And that's all very much a part of what was happening with the real estate — nobody was trying to live over in Dumbo when they were doing those parties, but afterwards, that's when the push in Dumbo happened and it got gentrified. But that was a hot moment there, those three or four years they were doing those festivals with illbient deejay music.

And they come out of a real important space in terms of that transitional moment under Giuliani, which is the Cooler [416 West 14th Street]. Because they got specifically targeted — the Cooler, and then Brownies [169 Avenue A], which was a real solid post-punk place. Both of those places got targeted by Giuliani. They revived the no-dancing law, an old Prohibition law, and they enforced it heavily. Especially at the Cooler, because they were they were trying to make the Meat [Packing] District extremely valuable to retailers and high-end boutiques. So they would send the Fire Department in with dogs to raid the Cooler and cite people for dancing, and they'd send undercover operatives in to snitch. It wasn't just by some natural law of attrition that all these places disappeared — they were seriously targeted.

What was interesting, though, and I don't think I was the only person who noticed this at the time, was that the Knitting Factory clearly had a special arrangement with the cops, because they were the only ones who could do hip-hop shows without getting raided.

Huh! That's interesting, because at least superficially, the Knitting Factory and the Cooler were very similar.

Yeah, but the difference was the Knitting Factory was also doing its big outdoor festival every summer, so they were getting major corporate and city support. They were plugged in in a way that made them un-fuck-with-able.

Giuliani was really a tipping point in terms of music in the city starting to get cracked down on by the police.

In terms of the Downtown incubator clubs, yeah. But by that time, hip-hop had become a multi-billion-dollar business. It didn't really need Downtown support or affirmation – it was a global phenomenon. And Living Colour [had become] a major corporate band. [Same with] Bad Brains, Fishbone. So, for people who have come in behind us, those avenues were a little bit cut off, but not completely. The Black punk bands – who were really the foundation of what became Afropunk - they were still playing Downtown and establishing their audience, and they really had the young moxie going on. The illbient thing was happening with major support. So people figured out how to survive without CB’s or Brownies - those scenes were already in the rearview by the mid to late ‘90s.

At that point, in terms of New York clubs that were hosting a lot of hip-hop, the ones that were getting a lot of attention mostly seem to be bigger spaces, like Tunnel or Building or Latin Quarter.

Knitting Factory was doing the more underground side of it, so it hadn't completely flipped in terms of perception. [But] here's the thing: It was difficult to put on a hip-hop show in New York City no matter what level, because the police had the venues requiring insurance. So even Madison Square Garden, after a certain point, wouldn't book a hip-hop show because of the insurance costs and the police harassment.

Do you see a connection between the changes in the economics of the city or the geography of the city, to what kind of music is being made?

I think my sense of the city expanded, because Uptown is undergoing this revival. And then Brooklyn was in a transition; a lot of young Black folks started moving to Brooklyn in the ‘90s. There was a lot of work inside of hip-hop journalism and the hip-hop industry, hip-hop-oriented record companies, and the neighborhoods were still affordable — you could still get a nice apartment in Fort Greene, Prospect Park, Flatbush, Bed Stuy, for like $1,000 or less.

That audience was definitely checking out different venues and situations. Like, Puffy had a regular club called Daddy's House.1 Folks that were in their early twenties were hanging out there. And there were different clubs like Nell’s [246 West 14th Street] where the Native Tongues, that generation, would hang out Downtown. Downtown was still viable, not so much for bands, but for folks who were following the hip-hop scene and the house scene: Sound Factory, Body and Soul, Shelter. That kind of transition in terms of musical tastes had already happened by the time we get to the mid ‘90s.

Why do you think it was that bands got pushed out of that area, but dance music, deejays, and hip-hop were still able to flourish?

Well, those clubs were really legit. Sound Factory, Nell’s – there was a whole lot of money behind them. The audience that was coming through was a little older, and a little more…I don’t know if I want to say “sophisticated,” but the dance audience is dedicated. Those folks came out every week to get that release. So, you got this parallel universe thing going on, building on what Paradise Garage had established.

But as you move into the 2000s, it's just a big cultural shift. There's just not a lot of support for a band culture, because that [younger] generation is gonna go out and do something else. The people who still have bands are the kind of people who want to be in a band. It's not even a career, it’s [just] an expressive thing.

You look at bands like Funk Face, Tamar-kali. There's a whole group of women who were doing a thing called [Sista] Grrrl Riots, who were coming out of out of punk and hardcore — they were still Downtown. Or a band like Apollo Heights, where there’s a whole connection to the UK shoegaze scene — they started doing that in North Carolina where they were from, and then went to England, and then came to New York. So these people are Downtown, but the scene is not the place, the place is not the scene. They are their own scene. What's going in the neighborhood doesn't really define them.

It's a funny thing, because that neighborhood still feels like a transitional neighborhood, or it did until it got both of those luxury hotels on the Bowery. You get down to where CB’s was and it's like, yeah, the men’s shelter still is still there, but it's next to John Varvatos, and Whole Foods is around the corner. You go over to Houston and, you know, the pizza places are still there, the falafel places are still there, Katz’s Deli is still there. The non-creative aspect of the neighborhood is still very present. The other stuff we might be interested in, the culture, it's dispersed.

If you want some of that Knitting Factory flavor, you can go hang out in Brooklyn, there’s different little spots. [But] someone from Brooklyn wouldn't necessarily go to Williamsburg. Williamsburg is pretty much established as a kind of a white millennial scenario. It’s not like they brought anything in with them that transcends no wave or punk or techno or house. They're still continuing on with the culture of the ‘80s and ‘90s, they’re just doing it with younger bodies.

But that’s where that class thing is reflected too, because those radical shifts in American culture generally come from the most desperate people in the vicinity. When people ask me “Was it better back then?,” I would say that young people now are having as much fun as we did, because that’s New York City. But I don't think we're going to get a Basquiat or a Rammellzee or a Public Enemy or Queen Latifah from the family-trust-supported generation of folks like the NYU students today.

It's funny, a couple of years ago, I went down…I used to hang out outside around the Voice all the time. I was pretty much known for keeping an office on the stoop of the liquor store at Astor Place, to the degree that people who would fly into the city who were looking for me, they wouldn't even call, they would just come down to the liquor store.

I hadn’t done that for years, so I went back down around Astor Place, and there was these benches set up there now outside of one of the new buildings. I decided to look at the kids who were walking up St. Marks on a Friday night, and I was just like, Alright, who looks like an artist? And on St. Marks, the fact that I'm even asking the question can tell you something. I sat there for about an hour, and then after about an hour, I saw three kids who were probably at NYU or Cooper Union, but you could tell they were probably going to drop out and do some renegade shit. But it was all these well-supported kids who can afford NYU.

And you know, there are these jazz education programs all over the city, all over the country — there's about 2,000 of them. In suburban America, the after-school jazz programs are just the shit. It's what kids want to do, man. But what blew my mind was finding out, wow, kids are spending $60,000 a year at the New School to learn how to play fuckin’ jazz and shit?! Like, most of these cats who are your teachers never made that in a year! And they had to figure a lot of it out. I mean, they [might have gone] to college, maybe got a basic conservatory education, but a jazz education, you didn’t have any choice but to learn that on the road and in the clubs. So once you know how much it costs to go to NYU to become some kind of artist, that kind of tells you how the neighborhood has changed.

So where can art and music thrive at this point?

Folks are making it happen where they go. Folks are there in Philly, in Baltimore, San Diego is becoming a hot place. There's a whole scene going on in Houston and Detroit. A lot of my cohort, who were part of the hip-hop/slam poetry scene in Brooklyn in the ‘90s, a lot of those folks broke out and went back home to Baltimore, Detroit, DC, Philly - so to the extent that there’s underground scenes happening, they're happening there.

And there's support there on a local level too, because now everybody's gotten the word that the only way you're going to have these cities survive is if they're culture-forward. Winston-Salem, Asheville, Durham – they become the new cultural artists’ spaces, because they're dealing with all this loss of manufacturing and all this open space. Nobody has to come to New York to try to make it as an artist.

Though I will say that with respect to jazz, this is still the star-making place. If you want to blow up a career in jazz, no other place else in America has a modern jazz scene where you're going to play with the best of your peers and have opportunity to go hang out with Jason Moran or Vijay Iyer, those folks. LA’s got its own scene [with] Kamasi [Washington] and those cats, but at this point, I don't know that the cats who aren't necessarily part of their generation are going to be able to ride their coattails. I think they're kind of back to square one.

But that's the way those things work: Those doors get closed behind cats when they make it out of the hood into the stratosphere. America has gotten so split between those on the progressive wave and those on the neanderthal wave, but to the extent that you can go to these places – Winston-Salem, Durham, Atlanta, Miami… I mean, Miami’s got a fast-gentrifying section that’s like a graffiti Louvre. By the time I got down there to see it, you could already tell [the neighborhood] was about to flip. It happened in such a compressed amount of time, it was like the time it took us to get from CB’s in ’75 to the John Varvatos store got compressed into a few months!

It generally seems like that cycle has accelerated.

Totally. There’s a place called the Africa Center on Museum Mile, and to make a long story short, they would have meetings with people trying to help them figure out how to raise money, but the people that were trying to raise money were connected to billionaire African telecom firms and the New York elite. The woman who started it was the wife of the Comptroller of New York. The thing I noticed by the time they brought me in, I just said, “You guys need curators, because you're not gonna get money from the money people being money people – they’re not interested in hanging out with other people like them, they’re interested in immortality. So [you] need that person who's the bridge between the artists, the public, and the money.”

They never figured it out. The money wants its name to live on attached to university buildings and law schools and cultural institutions. Carnegie Mellon, JP Morgan, that's what they did with all that money when they had maxed out being robber barons: They created the schools and libraries and museums that we have today. That’s what’s happening all over the country now, because people realize the future of American cities is culture. Particularly in the south, you’ve got all this Black culture was never recognized the first time around - artists like Thornton Dial and Lonnie Holley, they represent a whole movement that was completely overlooked because the cultural literati of the South was trying to find legitimacy in following Northern [trends] and completely ignoring the way stuff was going to shift.

Have you seen the exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York that just opened? [“New York, New Music,” which focused on various music scenes in the city between 1980 and 1986, was open from 2021 to 2022.]

Yeah, I just went there. It’s funny: People try to act like the music stopped at a certain point, because it stopped for the young white rebels at a time. But that’s when BRC and hip-hop were just getting started!

But largely because of what hip-hop did, what Basquiat did — this is the American dream — the American cultural sensibility in the 21st Century is Black and of color. It's Latinx, it’s Black, it’s hip-hop. So all these institutions, you can see them changing. A place like the Guggenheim now has two Black women running it, and they had five events that were Black-women-centric [over] the last two years: Carrie Mae Weems, Solange, Simone Lee. They’re kind of telling [you], this is where it’s at and where it’s going.

If you hang out with your successful Black artist friends in New York and go to their openings and stuff, you forget that the art world is just white. We've created our own kind of culture within it around these folks who've blown up, post-Basquiat. One of my Yale students took me to this meeting of Biennial curators, and [I was] the only Black person in the room who's not working for the museum. It was a conversation specifically about international curation at the Korean, the New Zealand, and Dubai Biennials, and all the people who are curating these things are white. I was like, oh man, I needed this reminder.

But fast forward seven years and it's a whole different scene at the Guggenheim, because these museums are finding that their older patrons are kinda phasing out. The kids aren't really interested in the visual art scene, so you got to figure out a way to make them want to still be supportive of the art museum.

We've covered the gamut here - CB’s to the Guggenheim! But if you want to talk about real estate, in terms of New York cultural shifts, Museum Mile is where the radical shit is going on right now. It’s not a hospitable New York for younger artists, but then it's a more hospitable 1% landscape for younger artists of color. Chelsea, Museum Mile - that's where the avant-garde shit is happening now!

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

---------------

Buy Greg Tate’s Flyboy 2: the Greg Tate Reader here

More information about the Black Rock Coalition can be found here

Order a signed copy of my book This Must Be the Place here

Book a walking tour here

A weekly party that Puff Daddy threw with DJ Funkmaster Flex at Red Zone (440 West 54th Street).

Greg Tate broke it down. That was wonderful. Thank you for posting.

Fantastic read, thank you