Joe Schick (Blue Rock Studios: Dylan, NY Dolls, Bette Midler, Ed Sanders, etc.)

"I always thought that Dylan pretended to write 'When I Paint My Masterpiece' in the studio to really freak Leon [Russell] out."

A few weeks ago, I got an Instagram message from one Joe Schick suggesting that I add Blue Rock Studios to my Soho walking tour route. I get messages like that often and welcome them whole-heartedly, but I do end up weeding out a lot of bad third-hand info, matters of preference, or simply suggestions for research I ought to do.

But this one intrigued me. Blue Rock, Schick explained, was the first 16-track studio in Soho, which he’d opened with partner Ed Korvin in 1969. He listed several high-profile sessions he’d engineered, the most immediately eye-catching of which were Bob Dylan (“When I Paint My Masterpiece” and “Watching the River Flow,” both included on Greatest Hits Vol. 2) and the New York Dolls (their earliest demos, which have since been released as Lipstick Killers: the Mercer Street Demos, even though the studio was actually one block over on Greene). More information was available, he offered, should I be interested in the stories behind the sessions.

Fuck yeah I was interested. Are you kidding me?! This is the kind of inside baseball shit I live for.

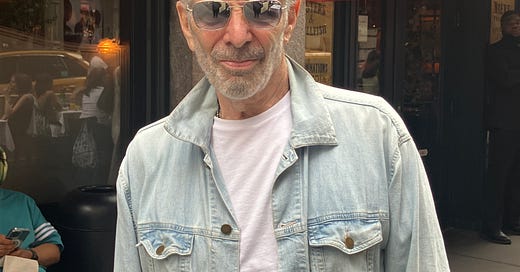

Schick left studio life behind in the ‘80s - he’s since had stints as a journalist, in city government, and event production, among other things - but clearly relished the opportunity to talk about things that, as he put it, “nobody ever asks about.” At his suggestion, we met for lunch in Soho - spitting distance from Blue Rock’s former address - and spent the better part of two hours talking about his six years at the studio.

Joe Schick, just after our lunch.

How did you get into studio work?

When I was in college, I was in a fraternity, and the role that I took on in the fraternity was the Keeper of the Sacred Jukebox. It meant that I got to select the records that went into the jukebox and that people would dance to and get drunk to and make out, and I took my job very seriously. I was already given to what you were probably given to, which was to find really fascinating, obscure music and champion things that others might not be aware of.

In 1965, the Zombies had a song called “Tell Her No.” At about two minutes and 19 seconds into that song, there was a sound that I couldn't get out of my mind, and I didn't know what it was. I was crazy about the song, and I decided that I wanted to make that sound. I didn't know how I was going to do it. I didn't even know what a recording studio was. It turns out that that sound was a tiny little hand clap deep in echo, which I only later figured out. But the idea that I could make sounds like that was extremely powerful to me.

So later on, I dropped out of law school, and my then business partner and I decided to build a recording studio. We were involved with a three piece blues band that was kind of a house band at the Electric Circus, called Sirocco, [and we] wanted to record them. We didn't want to go [to a studio] Uptown, because we were Downtown, we were longhairs. So we said, “Why don't we just build a recording studio?” A little bit of a delusion.

My partner, Ed Korvin, had some family connections, so we raised part of the money from his connections. I raised the rest of the funding for Blue Rock through convincing an equipment leasing company that they needed to be our supporters, without enough collateral to really make it possible. They lent me $500,000 of equipment on my [word], which was pretty cool.

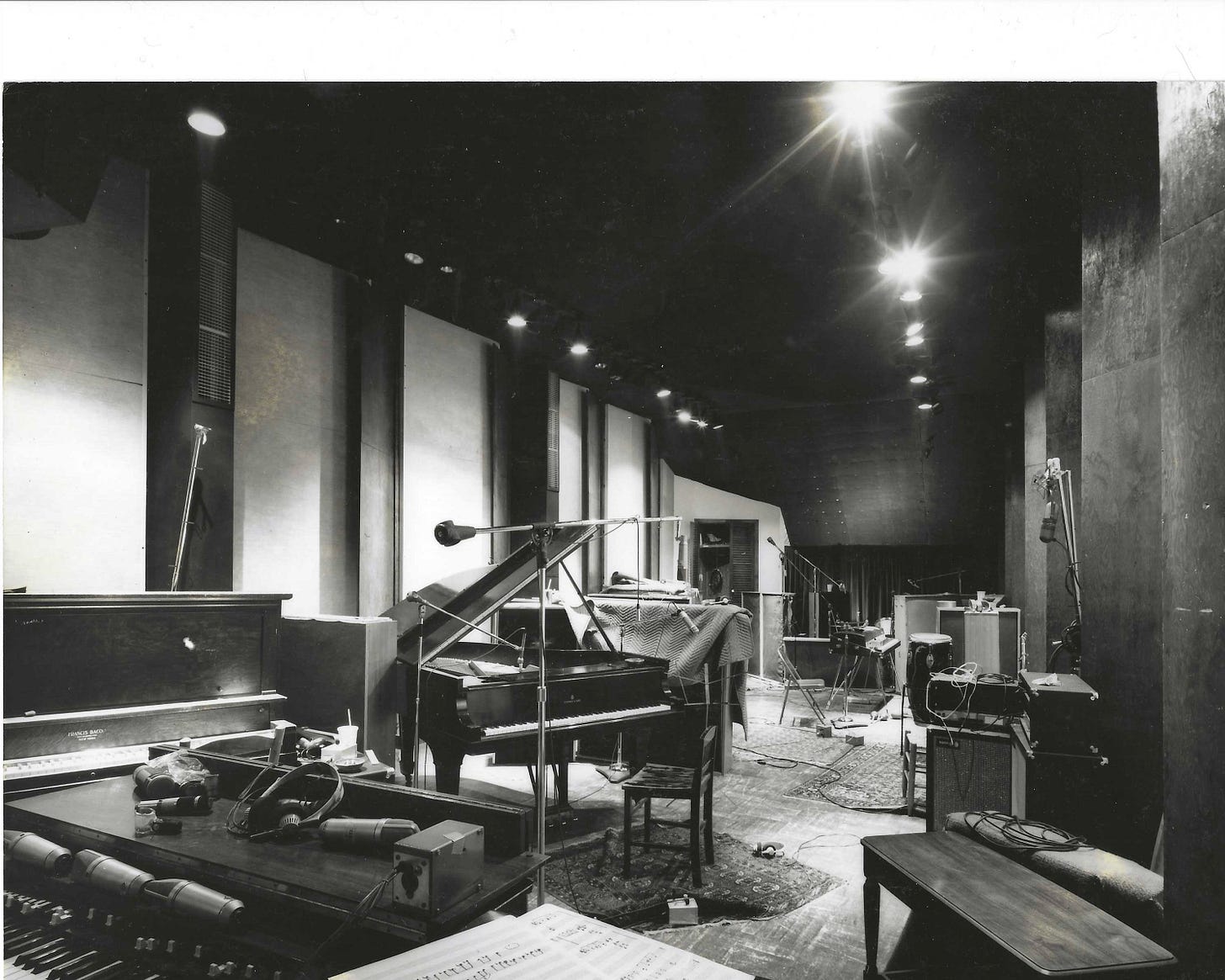

Blue Rock Studios, photo courtesy of Joe Schick

It took us about a year and a half to build Blue Rock, starting in 1969. After having searched for a number of locations, [we found] 29 Greene Street. By that time, we had found the architect for Blue Rock, John Storyk. John, exactly at the same time, was designing Electric Lady. So in effect, Blue Rock was the kind of ne'er-do-well little brother of Electric Lady.

At Electric Lady, Jimi [Hendrix] wanted things like Jimi wanted things, you know? Jimi decided that he only wanted circles in Electric Lady, so everything had to be spherical. When these expensive heavy metal doors were delivered to Electric Lady, they had horizontal windows in them, so Jimi rejected them. Storyk said, “You don’t want them, you can’t return them. Let’s just give them to Blue Rock.” So Jimi’s rejected studio doors became my studio doors.

My [construction] crew was all hippie carpenters, and my guys would go over to Electric Lady after work shut down for the day - because there they were working with union crews and grown up carpenters - and steal wood. So my studio was built with Jimi Hendrix's lumber. At the opening [party] of Electric Lady, I was outside smoking a cigarette, and Jimi was outside. He bummed a cigarette from me, and I told him, “Hey, man, I just want to thank you. Your lumber built my studio.” And he was like, “What??” [But eventually] he was like, “That's cool, man.”1

Our building was owned by two brothers, Danny and Paulie Castellano, who were affiliated with another venture altogether. I think it was Paulie who died in, they say, a mob-related shoot out at Sparks Steakhouse. I would go every month to give them the rent in cash, mostly to Danny. And they would always say to me, “Hey, kid, why don't you just buy the building? Give me 100 large, it's yours.” They liked me; for anybody else, it would have been like a quarter of a mill. But I never had the money.

Did you already know how to use all the recording equipment, or were you learning on the fly?

I had no idea what I was doing. I'd been to about three recording studios. Before that, we did some demos with Sirocco at a studio called Vanguard, and we went to a couple of Jimi’s sessions at the Record Plant.

A very strange guy named Duffy was supposed to be the audio engineer, but one day he just disappeared. Eddie Korvin and I taught ourselves how to engineer on the fly in maybe a three or four month period when the studio was [set up], but before we really launched.

Was the first session Sirocco?

I think Sirocco had broken up [by then]. But I’d become friendly with two guys who were part of a band called Dreams: The bass player, Doug Lubahn, who had been the bass player in the Doors’ studio sessions and played with Billy Squier for a long time, and his musical partner Jeff Kent, who was the songwriter and bandleader. I gave Bette Midler a song of theirs for her first album, [which] figures into this story sideways. A funky little number that Doug and Jeff wrote called “Daytime Hustler.”

Do you mean you introduced the song to her?

Yeah. She and I were dating. Bette Midler, then and now, enormously talented. She could have done anything, been any kind of entertainer she wanted.

Anyway, I used Doug and Jeff and the Dreams guys to test drive the studio. Billy Cobham was the drummer, one of the great drummers of New York. And then we gave away a lot of time to Downtown musicians. The first playing session was a song from the soundtrack of a Stacy Keach movie with Judy Collins.2 By 1970 it was kind of like, “We can do this, and it works.” People were using the studio, we knew how to engineer. We were getting paid for little demo sessions and stuff, but nothing came out.

But in early 1971, maybe January, somebody had told Bob Dylan's then-manager about us. I was kind of brazen, and I called the guy. He wasn't there, but his wife answered the phone, and I had a long conversation with her. I told her who I was, what I was doing, told her that the studio was five blocks away from where Dylan was living on [94] MacDougal Street. Bob was looking to do something outside of the world of CBS’s studios. She liked me, and the next day I had a conversation with the husband. The two of them were kind of managing Bob together, and she said, “I'll see if Bob wants to check it out.”

Then in February of 1971, at like 9:30 in the morning, there's a knock on the door. I was the only one there, so I went and opened the door, and there was Dylan. We were wearing the exact same hat - these Chinese communist border guard hats, with these huge fur flaps in the front. I mean, the exact same hat.

We looked at each other, and he said, “Do you mind if I come in and look around?” He did, [and said,] “Do you mind if I come back in like a week with a couple of guys?” I had never done a big time session, and neither had Eddie. I was expecting Dylan to bring Happy and Artie Traum, guys like that, or maybe David Bromberg. Dylan shows up, and the band is Leon Russell, Jesse Ed Davis, Carl Raddle and Jim Keltner. These are like the A List of the A List. I was like, I am in over my head.

It was very cold. We couldn't get a good sound for Jesse's guitar in the studio; he wanted a little more reverberant, natural sound. So we put him in the stairwell, going to the basement, which was unheated. It was really cold and he was really pissed off, but it made him play great. Listen to “Watching the River Flow,” his guitar [playing] is really brilliant.

This is the stuff that ended up on Greatest Hits Vol 2, right?

Two songs: “Watching the River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece.” I always thought that Dylan pretended to write “When I Paint My Masterpiece” in the studio to really freak Leon out. I don't know if that's true, but I always thought he was holding a little pad and pretending to think and write out lyrics, but he'd already written it. I don't know.

The other thing that people always ask is, What was going on with Dylan’s voice on those recordings? The mystery of Bob Dylan! He had a cold, that’s all.

If I listen to it now, I do actually like the mix. Leon did the first mix of those two songs, and then he left town. Bob called and asked if he could come back and remix “Watching the River Flow,” so I mixed “Watching the River Flow” with Bob. It was the first thing I'd ever done that got anywhere. And when I listen to it now, given what I knew and didn't know [at the time], it sounds good.

That's quite the trial by fire.

I was able to do a good enough job in translating it into a final piece of tape. There were at least three other songs [recorded at that session]. I think there were two George Jones songs, “The Race is On” and another one. And there was a pretty good version of [Ben E. King’s] “Spanish Harlem.” I don't know if any of those have ever found the light of day. They're obscure Dylaniana.

The original 16-track, 2” recording of all those five songs, and maybe more, was erased and taped over by my partner. We never had any money, so if we could erase tape and reuse it, we did. I think I was out of town when he trashed 16-track Dylan masters. However, later on that year, we got a summer assistant, a young woman who became my chief engineer in time. Her name was Jan Rathbun. Jan was kind of my protege, and she became a way, way, way better engineer than I ever was. She kept the 2-track ¼” Dylan master tape in her closet for 35 years, and last year we gave it to the Dylan center in Tulsa. There was a little ceremony where we handed it over.

“Our Day in NYC” by Skip Blumberg and David Cort (1973) includes footage of a session at Blue Rock, led by engineer Jan Rathbun, beginning at the 7:03 mark. Schick briefly appears around the 15:00 mark.

Did that Dylan session open up a lot of doors in terms of people coming in?

It should have, but I don't know that it did. People always were like, “How impressive was that?!” But I didn't know about marketing. I just thought everybody would figure out [where it was recorded and come use the studio]. But [musicians] would come by and hang out. Bette sang back up on things that I would bring her in for every once in a while. Melissa Manchester was in that world. Maria Muldaur was around all the time.

Stevie [Wonder] came once, did a demo, but then went back Uptown to Mediasound where his producers, Bob Margouleff and Malcolm Cecil, were [based]. Bob Marley recorded at Blue Rock. We always thought he did background vocals on some part of the Exodus album there, but I don't know if that's true. I was going away for the weekend; he came, because we had mutual friends, and I let him in. He stayed at Blue Rock for like three days while I was away, and all kinds of people came in to hang out with Marley and play for like 20 hours straight.

And then from people who heard about it through other people, Blue Rock kind of got momentum in a whole world of R&B stuff. The Fatback Band did a lot of work at Blue Rock with my partner, Eddie. He also made friends with these avant-garde jazz musicians, like Carla Bley and Michael Mantler, and worked with them a lot.

I'm curious about that New York Dolls session.

The Dolls’ manager was a guy named Marty Thau. I think I met Marty at Max’s Kansas City. Nobody knew who the Dolls were - they hadn't done anything. I think I gave him the time to do a one night demo session, which probably started around 10:00 and went ‘til about 8:00 the next morning. They were all fucked up - not in a terrible way, but they were definitely indulging as the night wore on, and it was very sloppy. It was also not my best night work-wise, possibly because I was indulging as well. But we all got along great. I think it was the first time they'd ever been in a recording studio.

The session was what it was, but it got really loose around 6:00 in the morning towards the end of the session, partly because they didn't have to [pay for it]. I got them to back me up doing, I believe it was “96 Tears.” I don't know what happened to that version, which is definitely for the best, because it would have been unrecognizable. I'm sure I was slurring my words. I would go see them after that, but I never had anything more to do with them professionally.

Is there a record that is the epitome of Blue Rock in your mind, that captures the spirit or sound of the studio?

One thing about the sound at Blue Rock, except for maybe 11% of all the time that I recorded there, the drum sound never made it for me. Something was wrong with the way that we configured the placement of the drums in the studio, and even if we moved it around, it never quite worked. I mean, some might say it did - Bernard Purdy didn't mind it, Billy Cobham didn't mind it. It just wasn't what I wanted to hear.

But around ‘71 - ‘72 I worked with a band from Pennsylvania called fred, lowercase f. It was a six-piece jazz rock ensemble, mostly instrumental. Like Mahavishnu, that kind of sound. And they were great. They would come from Pennsylvania in their van and camp out in the studio, and I did a series of demos with them over a year and a half or so. We ended up with these pretty high quality, polished songs, but the five deals that were percolating for about a year fell through, and then they broke up. The drummer from the band came to work for me at Blue Rock as my assistant.

But there was one single that we did with fred, I don't remember what song it was. It actually came out and wound up in a cut-out bin in Germany. Some esoteric collector found it and was like, Oh, I love this shit. Let me get in touch and see if there’s anything else that I can release. He found the songwriters’ names on the disc, and ultimately tracked one of them down. That led to a whole album of fred sessions being released in Germany in 2004 on this label called World of Sound. It fell back into obscurity, but how cool was that? It's not popular music, but it was great.

Another record that comes to mind was Ed Sanders [from the Fugs]. Ed had a record deal with Warner Brothers, which was strange. He came to me through a mutual friend who executive produced the record, but he had no idea what he was doing. It was called Beer Cans on the Moon, and I produced and engineered it. It’s justifiably obscure. I found it unlistenable. But Ed was, at the time, one of the founders of the Yippies, so Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman were hanging out at Blue Rock all the time, because the phone was safe. Our phone wasn't being tapped by the FBI. So there was a lot of anti war organizing done at Blue Rock without my official knowledge while Ed was making the record.

Over the course of the time that you were at Blue Rock, did the neighborhood change much?

It was clear that Soho was getting some traction. It was still principally an artist community. There weren't chic stores moving in, but it was clear that we were in the place to be, which wasn't clear in ‘69 when we started. And then there started to be bus tours of Soho, where people from out of town would come to see where the artists hung out. That's definitely a sign that things are happening.

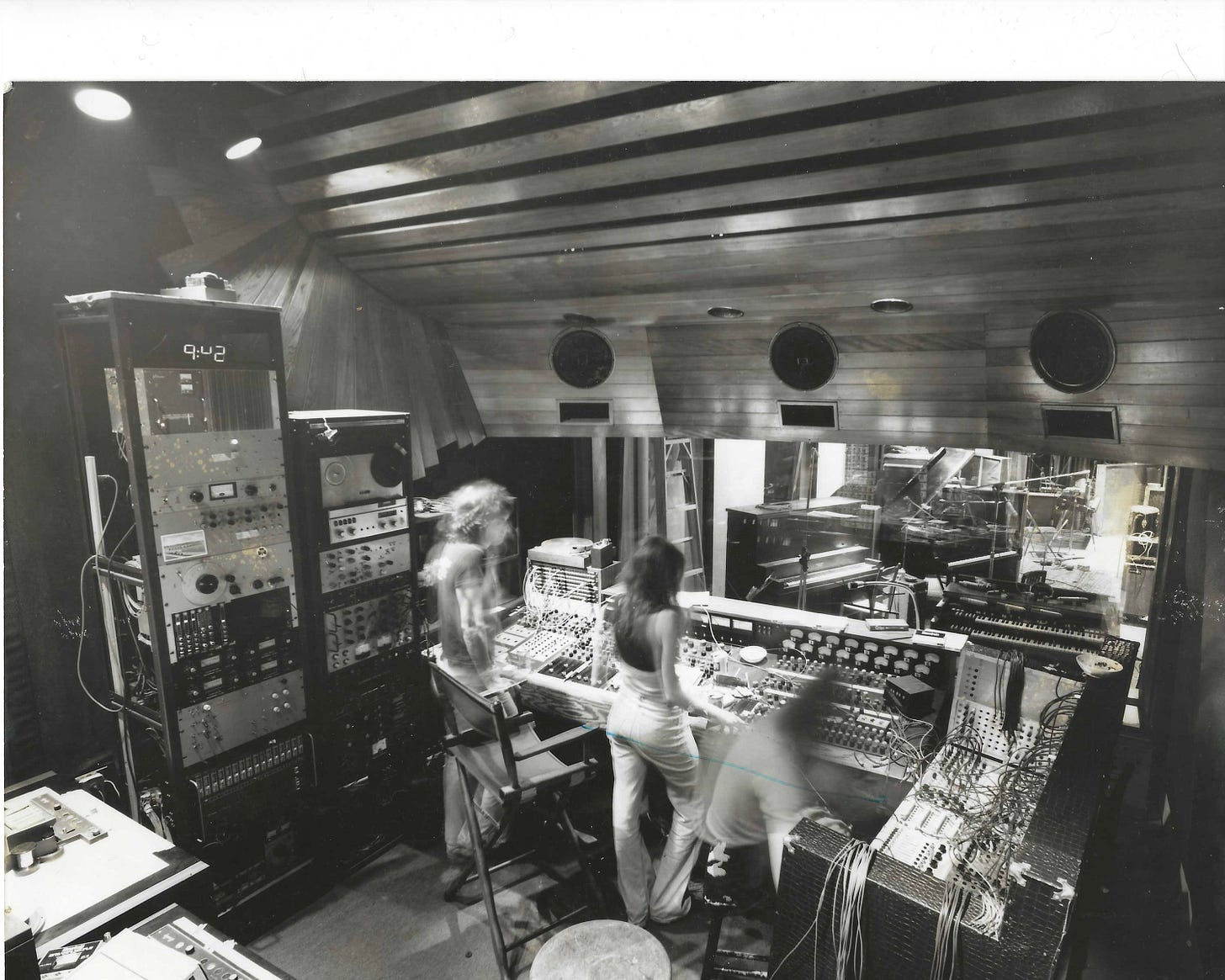

I left the studio in ‘75 and went to Bearsville. There were a lot of reasons. The mood of the music had changed. I also had business partner issues - my friend and I had grown up a little bit, and I couldn't envision a long term successful career together anymore.

[For example,] I went away for a week once in 1972 or ‘73, and I left my partner in charge; he was doing some obscure jazz thing. I was up in the mountains, and I was out of touch, and when I came out of the mountains, I called and spoke to Jan. I said, “So what's going on?” And she said, "Well, it's been a pretty quiet week. We had to turn down some sessions because Eddie was working with this obscure jazz artist.” I said, “Who did you turn down?” “James Taylor and Carly Simon.” That sort of sums up the Blue Rock experience.

Blue Rock Studios, photo courtesy of Joe Schick

I had been offered the opportunity to manage Electric Lady after Jimi died, which was right at the time when Electric Lady opened. I declined it, because I didn't see myself doing the management of a recording studio. I was more of a creative than a business hustler. But then Albert [Grossman] had heard of me through John Storyk and others. He offered me [a job running] the studios at Bearsville,3 and my girlfriend at the time wanted to leave the city anyway. I moved up there and ran all the rehearsal studios at Bearsville, I ran the touring equipment company at Bearsville, and it was a cool job.

Bearsville was great. The guys from the Band were around, Todd [Rundgren] was around although he was doing his own thing in his own studio. Paul Butterfield worked at Bearsville a whole lot. Paul borrowed the same $35 from me about 25 times. I would lend Paul Butterfield $35 and he would pay me back and borrow it again, like, a week later. He died owing me $35.

When you say the mood of the music had changed…

By the time I left Blue Rock, it was the early days of disco. Things had sort of moved in that direction, and it wasn't that I didn't like those things, it wasn't what I had originally signed up for.

For years afterwards, I would run into people who I didn't know, and they would say, “Man, I have to thank you. You gave me studio time. I made a demo, and I got signed.” People would buy me dinner!

Schick outside 29 Greene Street, the former location of Blue Rock Studios.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and context.

---------------

Buy a signed copy of my book This Must Be the Place here

Book a walking tour here

And of course, if you haven’t already…

Schick later wrote a biography of Hendrix under the nom de plume Victor Sampson.

In a follow-up email, Schick guessed that it was probably a demo of Collins’ “Easy Times.”

Grossman’s record label, Bearsville, and his studio complex, Bearsville Studios, were located upstate in Bearsville, NY.

Loved this one

Fascinating for an old fart like me.